Democracy and World Cup 2014: Brazil’s State of Emergency

Terra de Direitos

Fonte: Upside Down World

More than 10,000 police with military training are poised to counter any disturbance or social unrest which may occur before and during this year’s World Cup.

On December 20, 2013, Brazil’s Defense Ministry published a manual entitled “How to Guarantee Law and Order.” It encourages using military action to ensure “public security.” It also lists individuals, groups, organizations, and movements considered "opposing forces”, highlighting those whose actions violate "public order or public security.”

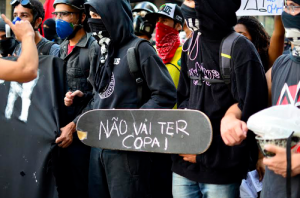

This unprecedented document, along with impending legislation, seeks to contain and neutralize any protests or expressions of democratic discontent around the World Cup. Protesters are equated with criminals, marginalizing them and denying their rights as citizens. Such was the case of the first demonstrations that took place in different cities in Brazil during January 2014. The military police arrested more than 143 people and used extreme violence against demonstrators.

The new manual gives police further power to invoke the three branches of the Armed Forces (Army, Navy and, Air Force) through a Presidential order which can be called for by state governments at any time. Its goal is to "provide security to facilities, equipment, and personnel involved or participating in major events."

Along with the military concept of “the enemy,” another conservative concept has been recycled from the era of the Brazilian military dictatorship, that of “the threat.” During the dictatorship, the concept of “the threat” was used to justify the persecution, repression, and harassment of activists and social justice organizers, not unlike the United States government´s labeling and subsequent persecution of alleged “terrorists.” According to the manual, “the threat” is characterized by acts or attempted acts committed by the aforementioned “opposing forces”, or by the general population that “potentially compromise the preservation of public order or the safety of persons and property.”

This idea of fighting an enemy or conquering a threat in the name of preserving public order is a convenient way to justify the series of laws, regulations, and rules which have been created in the three years following Brazil’s acceptance as host city for the 2014 World Cup. These laws make the 12 host cities (where the games will be played) into “exceptional territories for the free enjoyment of FIFA and its sponsors.” This framework of laws, which in many cases nullifies the Brazilian Constitution, was built unilaterally and without the input of social movements.

"There’s no doubt that the targets of the manual are protesters of the World Cup. All spheres of government are making sure that the World Cup takes place and, if possible, the world doesn’t see any protests,” says Luana Xavier Pinto Coelho, representative of the National Urban Reform Forum which a body of social movements fighting for the rights of citizens and for the reclamation of public space. She also warns that, "The freedom to express yourself is part of a democracy and it can’t be compromised. Increased police repression is a historic setback to freedom in this country, and in spite of it, collectives and groups will continue going out to the streets.”

Demonstrations against the Cup protest the public spending on infrastructure and the huge profits they generate for transnational investors, while much of the population lacks the most basic services: transportation, health, education, and job security.

Anti-terrorism Law: For Whom?

Within these measures that have been taken around the World Cup, the most pressing matter is a bill which is currently in an advanced stage in Congress and which would create the crime of terrorism in Brazil. Its text defines terrorism as “causing or spreading terror and panic affecting life, physical integrity, health, or liberty of citizens.” The problem is that this definition of terrorism is vague and can be embedded into any accusation. For example, a protest outside a stadium where a game will be taking place could be considered to generate "widespread panic.”

The application of anti-terrorist laws in Latin America has been dubious. In Chile, for example, the country’s anti-terrorism law has been used to criminalize social movements, such as that of the Mapuche indigenous group.

"Brazil is a country with no history of terrorist acts, and in principle, criminal legislation could lead to the excessive use of force during street clashes. It’s difficult to understand, therefore, why there’s the need to criminalize conduct that’s not part of the Brazilian reality. The only reason why the bill has moved quickly through Congress is this interest to apply such a law during the World Cup,” said Pinto Coelho. "The state of São Paulo, for example, has created an exclusive police force to police the World Cup and a special counter-terrorism force. If we don’t have terrorism in the country, towards whom is this apparatus directed?”

Senator Romero Juca (PMDB-RR), Rapporteur of the Joint Committee on Legislation and Regulatory Devices of the Constitution (a group composed of senators and congressmen), admits that Congress will try to make sure the legislation is passed before the start of the World Cup on June 12. He argues that the country needs this security in order to host thousands of tourists during the event.

Under this law, anyone convicted of terrorism could get sentences ranging from 15 to 30 years in prison. Additionally, terrorism would be a crime in which the accused could be held without bail and without the possibility of amnesty or pardon. The bill will be placed on the Senate’s agenda in February and afterwards passed on to the House of Representatives.

Criminalizing Assembly

Another modification in the criminal law is to change the crime of gang affiliation (through Law 12.280/2013) to the charge of “criminal conspiracy”, which would be easier to apply against protestors. It makes it easier to equate the act of assembly with crime.

For Argemiro de Almeida, a member of the National Coordination of Popular Committees for the World Cup (Ancop), "During the huge protests in June, the government showed that it wasn’t ready - and maybe still isn’t - to deal with political demonstrations. It erred on several occasions in several cities. This contributed to an increase in uncontrolled violence. Police presence prompted more violence. The increased militarization that we’re seeing is not the solution. "

World Cup Economy

The World Cup General Law (Law 12.663 of 2012) is the main legal framework that is responsible for giving FIFA and its associates a temporary monopoly on Brazil’s economy. The law anticipates “exceptional crimes” which will only be relevant until December 31, 2014. These include: Misuse of Official Symbols; Ambush Marketing by Association; and Ambush Marketing by Intrusion. It also provides for the creation of special courts to rule on lawsuits regarding the World Cup. Additionally, the law protects FIFA from any procedural expenses, while Brazilian citizens are left to foot the bill.

Furthermore, during the Confederations Cup last year a judicial precedent was set to ban demonstrations for the 2014 World Cup. The court of the state of Minas Gerais also banned demonstrations during the Confederations games.

Judicial Exceptions for FIFA

The World Cup General Law suspends Brazilian laws which guarantee citizens’ freedom of movement, repeals a law prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages in stadiums, and restricts workers’ rights to strike. In addition, FIFA has been assured exclusive rights to advertisement, sale, and distribution of products within a radius of two kilometers around the stadiums.

"While soccer stadiums are being massively transferred to private management through concession contracts, street vendors and public markets will be prohibited in these areas, to make way for franchises like McDonald’s [one of the sponsors of the World Cup]” said Pinto Coelho.

The law provides for the automatic granting of entry visas and work permits to anyone FIFA chooses and to anyone with tickets. With this provision, Brazil forfeits its power to control foreigners entering the country. FIFA and its associates are also granted tax breaks through the law. That is, FIFA and its sponsors do not need to pay federal taxes and import fees, and are also exempt from payroll taxes.

"The Brazilian government has accepted, with little resistance, all that FIFA has asked for, including regulations that defy national law and the Constitution, an affront to Brazil’s sovereignty. Representatives from FIFA in Brazil are received with Head of State honors. Additionally, FIFA has criticized Brazil’s infrastructure, but hasn’t invested a penny in the country. Instead, the Brazilian government has given it tax exemptions,” added Pinto Coelho. “A successful international event would project a certain image of the country to the world - an image of progress and development. This is what Brazil wanted so badly in 2007. I believe the government will do everything to make this image a reality. But the world will also pay attention to the peoples’ criticism of the World Cup."

In a statement, ANCOP also criticized the government's actions and characterized their position as political allegiance:

“The General Law of the World Cup is a response to FIFA’s demands. The argument that the Brazilian government made these decisions alone is unacceptable because the government has no authority to make international agreements without the Legislature. This is in direct opposition to our Constitution and laws. In the name of business and profits, we sense political favoritism towards FIFA, which harms our sovereignty, our domestic legislation, and our national interests."

The Marketing of Cities

Citizens are preparing to present illustrious images of their cities to the entire world as they play the part of proud hosts to FIFA. This is part of the marketing of these cities, and seen as necessary to attract investments.

"With this marketing, there began a broad process of hyper-regulation in cities in order to inhibit or prevent certain uses of public space,” said Pinto Coelho. “This includes a growing intolerance of itinerant workers, those who sell goods on the street, the homeless, street artists, etc."

The image adorned by Brazil’s cities will surely reflect what has been temporarily scrubbed away. A presence will remain, illuminated by the absence of the vendors and street denizens. A yearning has been discerned and will surely persist among Brazilians who have seen their democracy truncated before the looming apparition of the World Cup.

Actions: Impactos de Megaproyetos

Axes: Earth, territory and space justice